Field Study: Evergreen Brickworks

Emphasizing hands-on, real-world learning experiences, (a place-based) approach to education increases academic achievement, helps students develop stronger ties to their communities, enhances students’ appreciation for the natural world, and crates a heightened commitment to serving as active, contributing citizens. – David Sobel, 2004 (Skoutajan, 2012)

I’ve grown up exploring the outdoors. Some of my most favourite school memories, in fact, did not take place in school at all, but at outdoor education centres where we participated in scavenger hunts, horseshoed, learned how to make candles, and listened to stories on bales of hay. Additionally, my most vivid learning experiences similarly took place while gazing at the night sky, or collecting bugs, skinks, snakes, and plants, or simply observing the waves.

As such, seeing my own son embark on his own educative journey, place-based education (what I otherwise often refer to as outdoor education), always seemed to me an intuitive way to enrich his understanding about the world. Now with the added gleanings through my teacher education programme at OISE, I have greater understanding why it is a critical way to connect students not only to their communities, but to nature, and the world at large.

(RE)DISCOVERING EVERGREEN BRICK WORKS

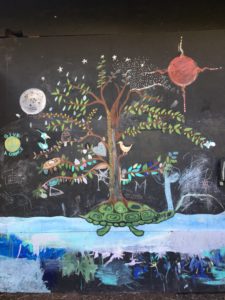

As such, I was excited to find out that we would participating in a field study at Evergreen Brickworks as part of my cohort’s Social Studies class (you can see the pictures @Ms_Ks_Korner). I had spent some of my summer biking and exploring the area and the market. I appreciated its unique design, and green spaces, but had little knowledge of its historical significance as a brick factory to my home city (Toronto). Additionally, we learned from our guide that once a quarry and brick factory was shut down, it turned into a makeshift gathering spot for underground parties (a testament evidenced by its many remaining graffiti tags). Soon after, however, community members reclaimed and fought to restore the space to its natural habitat – no easy undertaking.

Some of this insight came by way of a documentary we screened in class Brick by Brick:

A lot of it came by way of our wonderful educational guide who walked us through the grounds explaining significant points along the way that can in and of themselves be explored in greater detail with our own classes. We learned about the four sacred Indigenous plants growing in a garden, and throughout the grounds, as well as about how simple, pointed efforts turned local pond waters from something toxic to thriving habitats.

As Evergreen’s website reminds, school visits are approached with place-based, ecology-focused, hands-on, arts-infused, mobile, and integrated approach.

The experience served as a “living document” testimony to other ways of being and knowing – beyond those imposed by an industrial vision. It is an example of how mobilized community members have the potential to transform a space where otherwise it might have been left and forgotten. This restoration in turn wonderfully connects to Indigenous understandings of plants, and working with the land – as opposed to merely on it.

SCHOLARSHIP CONNECTIONS

Place-based learning is “where the curriculum lives….it is significant gains in student achievement that proves its immeasurable impact….If we can consistently connect the concepts students learn about with relevant and meaningful issues or activities that happen in our neighbourhoods and communities, we know the connections will be lasting and meaningful” (Skoutajan, 2012, pp. 34-35). This was my own experience, as a Teacher Candidate undergoing a teacher education programme on Social Studies & Aboriginal Education, learning how to teach in an anti-oppressive, social justice-focused way. Evergreen Brick Works allowed us to experience an alternative style of classroom, that very much demonstrates the value and concepts of traditional indigenous knowledge, as well how beneficial (and engaging!) such experiences can be for students (this one included).

Because Evergreen Brick Works is part of my own community, it is also a demonstration of how students can engage in the world around them and how they may see their own neighbourhoods with new eyes. Sometimes, going outside can make all the difference, academics aside. As Skoutajan (2012) finds, such opportunities can also help students better deal with stress and resolve conflict “The research clearly indicates the almost therapeutic and medicinal value nature plays” (Skoutajan, 2012, p. 35). Furthermore, “students involved in the outdoor education program demonstrated very positive feelings about science and the natural environment but also in their English language development and personal and social skills including conflict resolution, self-esteem and cooperation” (Skoutajan, 2012, p. 36). And what teacher would not want their students honing their emotional and social intelligence? But Skoutajan raises another important point – one I’m inclined to agree with:

“If we expect our students to become free thinkers and problem solvers who can adapt to the new parameters of time, space and resources then shouldn’t we be aligning our educational system more towards immersing our students in the community where real, authentic and meaningful experiences can be had?” (Skoutajan, 2012, p. 36).

SPRINGBOARD FOR SOCIAL STUDIES CLASS CONNECTIONS

“When students learn within the confines of a classroom, they are prevented from making real life connections” (Skoutajan, 2012, p. 36).

Our trip to Evergreen gave clear examples of how I may integrate place-based learning into my own practice. One memorable takeaway is how beautifully the grounds demonstrate the success of efforts to reclaim and repurpose prior industrial damage. Other place-based learning examples may include students creating enrichment toys for parrots, warthogs, and porcupines at a local zoo (Sobel, 2004, p. 55), or considering how polluted areas in their own communities may be changed for the better, with actionable plans that make real-world impact. It is an example of how mindful efforts can transform our communities, collectively, for the better – and how multiple ways of knowing can fortify such efforts.

Field studies are ripe with opportunities to address disciplinary thinking concepts outline in the Ontario Curriculum guide (Ontario Social Studies & History Curriculum, pp. 12-13). Evergreen Brick Works specifically easily connects Social Studies with Cause and Consequence (environmental degradation and pollution, industrial development and abandonment), Continuity and Change (reclamation, ecological restoration), as well as Interrelationships and Perspectives (Indigenous knowledge of plants and ecology).

But even as Social Studies connections abound (whether they be History or Geography-based), such a trip is a reminder that environmental education provides opportunities for cross-curricular connections too. Students can use their understanding of Math and Art to research and design bird houses, and student can investigate whether using 100 per cent postconsumer waste paper in our copiers is worth the cost” (Sobel, 2004, p. 63).

Another way to make real-world community connections as inroads to place-based learning is to forge partnerships with higher education institutions, diverse community organizations and other environment learning centres, in a way that allows students to take on meaningful roles that are valuable to the community at large (such as the document restoration efforts at a heritage home mentioned in our January 16th, 2018 class by our professor Rose Fine-Meyer, or by having students rebuilding a rope course that got destroyed during a storm). But in making such connections, perhaps other even more critical connections exist: Because, ultimately, “Place-based education is about connecting people to people, as well as connecting people to nature” (Sobel, 2004, p. 63).

References:

“Brick by Brick” by Hungry Eyes Media Inc. on YouTube, 22 Mar 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3gzgiYUzzW8

Skoutajan, S. (2012). Defending place-based education. Green Teacher, (97), 34-36. Retrieved from

http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/1095774877?accountid=14771

David Sobel. (2004). Place-based Education: Connecting Classroom and Community. Nature Literacy

Series 4.

Ministry of Education (2013). Ontario Social Studies, History & Geography Curriculum. Retrieved

from: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/sshg18curr2013.pdf